|

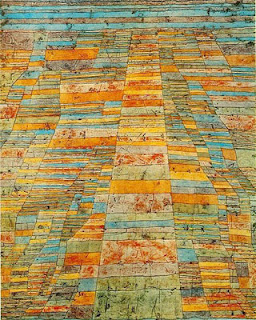

| Paul Klee, Mai Bild, 1925 |

This huge exhibition

of Paul Klee, L’Ironie à L’oeuvre is

the most calming exhibition I have been to in a long time. If you are in need

of an end of the week de-stress, this is the top floor of the Pompidou Centre

is the place to go. Rarely is modern art with its fragmentations and

abstractions so quiet and gentle as it is on Paul Klee’s canvases.

What I loved most was the fact that the paintings and drawings

were often incredibly angry and ascerbic, and while filled with fragmentation

and division, they are also yet executed with lightness and joy. In form, the work is very delicate: each

stroke and line is made of water colour, and they are painted often on

cardboard or paper pasted onto cardboard to accentuate ephemerality. In these

materials, there is a sense of transience to the works and, at times, it feels

as though they are going to disintegrate soon, as though they will crumble in

the hand if touched. Indeed, the Angelus

Novus (1920) a work barely known in its time, but that was made so famous by Walter Benjamin's discussion of it as the Angel of History in his Theses on the Philosophy of history, is so fragile that it is put in

a darkened room and will be returned to the lending gallery before the

exhibition is over.

Every work and every series of works is filled with

contradictions: the shapes and patterns are always geometrical, but not mathematical

or precisely drawn. In other contradictions, the sense of the childlike - but

not childish - that is everywhere in the air at the time Klee is painting,

becomes merged with the mechanical, with the machines that are also beginning

to appear everywhere in his historical moment. And Klee is also able to bring

the lightness, joy and play together with the critique of war spawned by

modernity in his midst. Indeed, there are many ironies here.

What’s also striking is the singularity of Klee’s work. Klee

does something quite different from other painters of his time, though there

are many references and resonances. It’s possible to identify his contemporaries

in the geometricality, for example, the use of line in its contrast with shape

and colour. There are also obvious references to work of Alexander Calder in

the magic and game-like nature of what Klee depicts and the way his mind works.

But then the colours used by Klee are always different from everyone else’s.

And the aggression, or what I would call the male-ness of the images that is so

prominent in his contemporaries, is absent from Klee’s painting. His images are

small, delicate, and I want to say, they are feminine in their tenderness.

|

| Paul Klee, Angelus Novus, 1920 |

And yet, that said, the most compelling of Klee’s works are

those produced side by side with cubism and constructivism. Though the latter can

be seen in the works produced when he was in Egypt, a time that he was more

interested in exploring the colours and textures of the desert. That is, it’s

is of course ironic that the influences of the most contrived artistic forms

appear in Klee’s paintings when he was closest to nature. I also wondered

whether the paintings’ continual verging towards two-dimensionality in Klee’s

later years a push to abstraction that mirrors the artistic response to

outbreak of World War II, or is it his own individual search? Because of these

apparently irreconcileable contradictions, while the exhibition is very calming

and peaceful, we come away with a lot of questions and I, for one, was

unsettled as well as restored.

No comments:

Post a Comment